Veterans Day began after WWI as Armistice Day, with real hopes for an enduring American peace

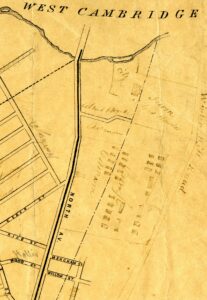

Above image: Massachusetts soldiers, including veterans from Cambridge, march in the state’s Armistice Day Parade on Nov. 11, 1929. (Photo: Digital Commonwealth)

By Beth Folsom

Just over a century ago, on the 11th hour on the 11th day of the 11th month (Nov. 11, 1918), formal hostilities ended in the First World War when an armistice with Germany went into effect. Known originally as Armistice Day, this holiday was meant to honor those who had served in the U.S. Armed Forces during World War I and had been discharged in any manner other than dishonorably.

Although Nov. 11 was celebrated by much of the American public from its first anniversary in 1919, it was in 1938 that the day became a legal holiday by an Act of Congress and known formally as Armistice Day. In 1945, following the end of World War II, army veteran Raymond Weeks had the idea to expand Armistice Day to celebrate all veterans, not just those who died in World War I. Weeks led a delegation to Gen. Dwight Eisenhower, who supported the idea of National Veterans Day. The day took on this broader significance over the next decade and, in 1954, it was formally renamed Veterans Day.

Massachusetts was one of the first states to adopt Armistice Day as an official holiday, beginning with Gov. Calvin Coolidge’s proclamation in 1919. Local organizations, including groups such as the American Legion, the Elks Club and area churches, used the occasion to host commemorations in the form of parades, concerts, balls and sermons. On Nov. 11, 1919, Cambridge Mayor Edward Quinn declared that there would be a public gathering in front of City Hall, featuring representatives from the current army and navy departments as well as members of the Grand Army of the Republic (veterans of the Civil War) and Spanish American War Veterans. The event featured a reading of the Declaration of Independence and concluded with the singing of “The Star-Spangled Banner.”

It was clear from this first Armistice Day celebration in Cambridge that the holiday would not be limited to those who had served in World War I. In fact, with the population of soldiers from the Civil War and Spanish American War eras disappearing rapidly, the institution of a new holiday to honor military service took on a wider and more important meaning in helping to keep public memory of those earlier struggles alive. Over the past century – beginning well before the official shift from a World War I-specific holiday to a broader Veterans Day – Armistice Day commemorations have routinely included celebrations of all who had served in the Armed Forces, regardless of period.

As the world moved through an economic depression and into another world war, Armistice Day took on a new meaning, marking both the enduring hope of peace and the perilous threat of war. The fact that the United States again found itself embroiled in a global conflict not a quarter-century after the peace of 1918 caused many in Cambridge and around the country to question the continued celebration of Armistice Day. In November 1946, just over a year after the end of World War II, congressman-elect John F. Kennedy spoke to members of the Cambridge American Legion at their annual Armistice Ball. Kennedy remarked, “And now once again the soldiers and sailors and marines have come home – and Armistice Day now honors the dead of another war. Once again there are Cambridge boys among them.” Kennedy’s message to his listeners that night was one of cautious optimism, expressing hope that the world had learned the importance of international cooperation and mutual goodwill from its second foray into global warfare, if not from its first.

In 1954, the year that Armistice Day was formally changed to Veterans Day, the Cambridge Chronicle reported that a rally would be held Nov. 11 to support the United Nations Charter Review. Created in the wake of World War II to solidify a commitment to international peace and cooperation, the United Nations proved to be both inspiring and divisive during the Cold War era. Many in Cambridge and beyond felt that such an international body was the only way to ensure peace, but others felt that the U.N. would give too much power and influence to the Soviet Union and China, both of whom operated under Communist governments that the United States was eager to stamp out.

Other, seemingly smaller changes in the way Veterans Day was commemorated also proved divisive within the city. A 1971 article in the Chronicle states that “Cambridge Veterans of World War I still have a lot of fight left in them. They are hopping mad over the fact that the observance of Veterans Day, originally World War One Armistice Day, has been pushed back from the historically accurate date of Nov. 11 to a Monday in October.” The article’s author goes on to compare the changing of the holiday (it was soon returned to its original Nov. 11 date after public pressure) amounted to the kind of “rewriting of history” of which the Soviet government was guilty – hardly the example Americans should want to follow.

In Cambridge, as in most American cities, World War I has been overshadowed by the legacies of the Civil War before it and World War II after it. Although the United States gave monetary and military aid to our allies for almost the entire course of the war, the country was only directly involved in fighting from 1917-1918 – none of which happened on American soil. Because it was so closely identified with Europe and its colonies, World War I received relatively little attention in the public sphere after the first few years after its end. The looming economic crisis that would become the Great Depression, which in turn segued into the Second World War, meant that World War I got short shrift in the area of public commemoration. In fact, the only significant memorial to the Cantabrigians who fought in World War I is a work by Boston sculptor Karl Skoog, “The Supreme Sacrifice,” which was installed in the Cambridge Cemetery in 1922. Because this sculpture sits on cemetery grounds, instead of in a well-traveled location such as Cambridge Common, it – and the city’s history in World War I – remains elusive.

As we prepare to once again mark the Veterans Day holiday, it is worth remembering its origins as Armistice Day and understanding the sense of hope that accompanied the end of World War I and what the world hoped would be a new dawn of international peace and security.

How has the meaning of Veterans Day changed over the past century, and how have those changes affected what Cambridge commemorates and whose stories we tell? Has the incorporation of other wars and the experiences of other veterans changed what Veterans Day means and how we celebrate it? Does World War I and its legacy still matter to America? To Cambridge? What do you know about the First World War and its impact on Cambridge – and what would you like to know? Share your comments and questions with History Cambridge here. You can also sign up for our newsletter to find out more about our upcoming events and public programs.

Beth Folsom is programs manager for History Cambridge.

This article was originally published in our “Did You Know?” column in Cambridge Day.